On a clear winter’s evening in Northumberland, the night sky can feel unusually rich and dramatic. Even to the unaided eye, winter seems to bring more bright stars, stronger colours, and some of the most recognisable patterns in the heavens. This is no illusion. Winter really does give us a privileged view of our local region of the Milky Way.

At the heart of it all is Orion, the great hunter, surrounded by some of the brightest and most colourful stars in the entire sky.

Orion: a cosmic signpost of winter

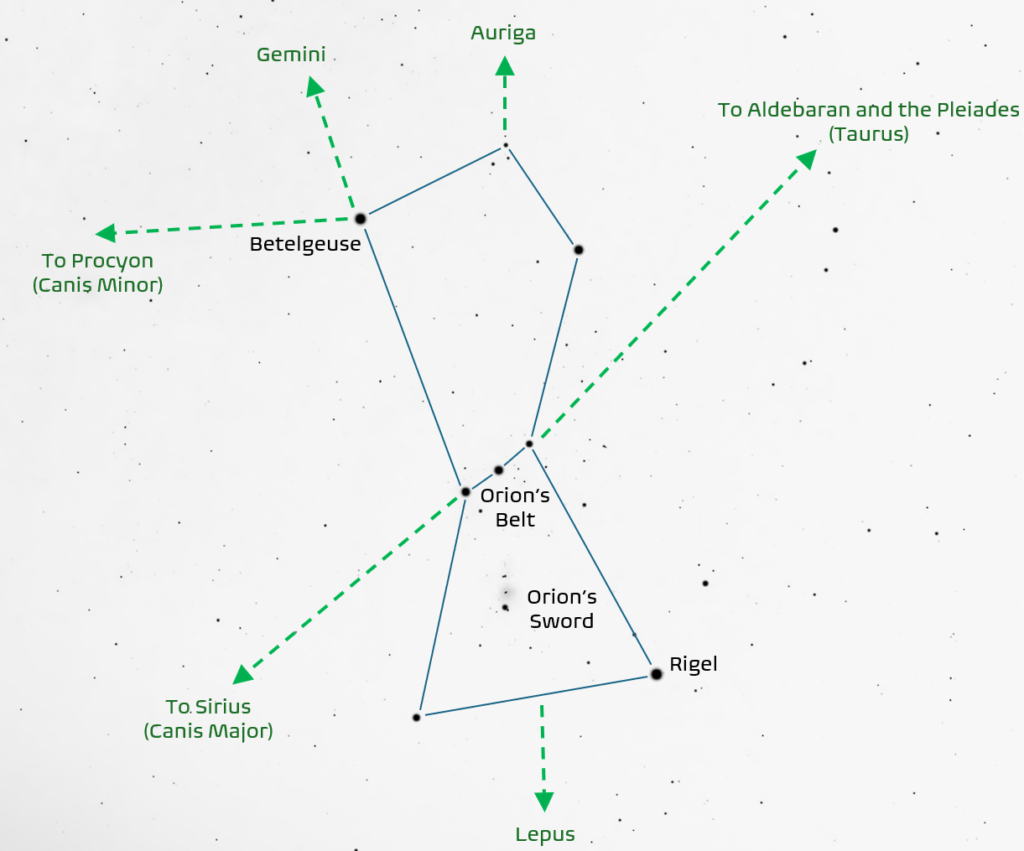

Orion rises in the east during autumn evenings and dominates the southern sky on winter nights. It is easy to recognise by the three evenly spaced stars of Orion’s Belt, with brighter stars marking his shoulders and feet.

But Orion is more than a pretty pattern. He sits in a vast stellar nursery, a region where new stars are actively forming.

Hanging below Orion’s Belt is a faint, misty patch of light: the Orion Nebula. To the naked eye it looks like a fuzzy star, but binoculars or a small telescope reveal glowing gas clouds lit from within by newborn stars. Even at a distance of around 1,300 light-years, it is bright enough to be seen from rural skies, and on dark nights in Northumberland it can feel almost three-dimensional.

This is winter’s great gift: we are looking into one of the nearest star-forming regions to Earth.

A palette of stellar colours

Winter skies are especially striking because many of the brightest stars show distinct colours. This is not an effect of Earth’s atmosphere or light pollution — the colours are real.

Betelgeuse – a fading red giant

At Orion’s shoulder glows Betelgeuse, unmistakably orange-red. This colour tells us the star is relatively cool at its surface (by stellar standards) and enormous in size. Betelgeuse is a red supergiant, nearing the end of its life. Its colour comes from its cooler outer layers, which emit more red light than blue. Betelgeuse will eventually explode as a supernova. It is likely to happen in the next 100,000 years. Astronomically speaking – this is very soon!

In the meantime Betelgeuse continues to intrigue astronomers. In 2019 Betelgeuse dimmed in brightness by about 30% for about a year. The cause of this great change in brightness was attributed to a cloud of sooty material ejected by the star along our line of sight. More recently, a group of astronomers uncovered evidence for a small star orbiting very close to Betelgeuse – and possibly inside the outer layers of the star itself. This companion has been provisionally named Siwarha.

Rigel – hot, blue, and brilliant

At Orion’s foot shines Rigel, almost the opposite of Betelgeuse. Rigel is blue-white, indicating an extremely hot surface. It burns through its fuel at a ferocious rate and shines with tens of thousands of times the Sun’s luminosity. Like Betelgeuse – Rigel will end its days in a violent supernova explosion.

Sirius – the winter sky’s beacon

Low in the south-east, flashing fiercely, is Sirius. Known as the “Dog Star”, Sirius appears white-blue and often twinkles with rainbow colours when it is low in the sky. Its intrinsic colour is blue-white, again a sign of a hot surface, but its intense brightness and low altitude exaggerate atmospheric effects.

Sirius has a dim companion visible through large telescopes: a white dwarf star called Sirius B. You may prefer its nickname: the Pup! The Pup orbits Sirius with a period of 50 years. The two stars of the Sirius system formed at the same time around 200-300 million years ago. The Pup was originally the bigger of the two stars. It burned through its stellar fuel more quickly and became a red giant after 100 million years. It expelled its outer layers leaving the inert core we see today. Sirius A, the bright star we see today, will undergo a similar fate in the future, ending up as the second member of a binary white-dwarf system.

Sirius tends to twinkle madly when seen low above the horizon. When Sirius is low, there’s a lot of atmosphere along your line of sight. The atmosphere is turbulent and constantly moving and this causes starlight to bend along different paths, and for the white light of the star to split into its constituent colours. You draw these colours out by taking a long exposure of Sirius while shaking the camera!

Procyon – quietly nearby

Not far from Sirius is Procyon, softer white in colour and closer to us than most of the winter stars. Procyon’s gentler hue reflects a surface temperature not too different from the Sun’s, though it is larger and more luminous. Procyon also has a white dwarf companion star just like Sirius.

Aldebaran – the eye of the Bull

In the constellation Taurus shines Aldebaran, glowing warm orange. Like Betelgeuse, Aldebaran is a giant star that has exhausted hydrogen in its core. Its colour again tells the story of cooler surface layers and advanced age.

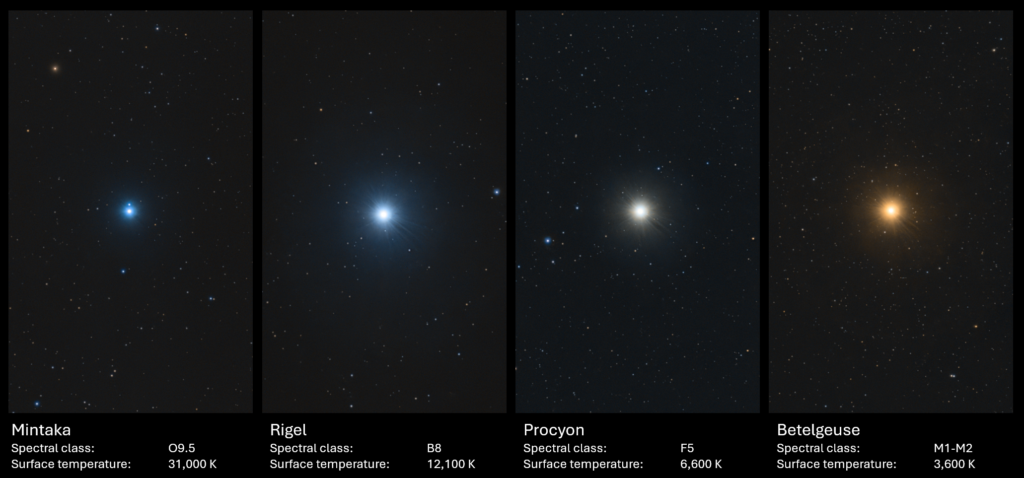

Why do stars have different colours?

A star’s colour is mainly set by its surface temperature:

- Blue stars are extremely hot

- White stars are moderately hot

- Yellow stars (like the Sun) are cooler

- Orange and red stars are cooler still

In everyday terms, it’s the same reason a hot metal glows blue-white while a cooler one glows red. Winter is special because it places many stars of very different temperatures side by side in the sky, making the contrast easy to see.

Navigate the winter sky

The stars of Orion form a very memorable pattern in the sky. You can use the pattern to point towards other bright stars in neighbouring constellations.

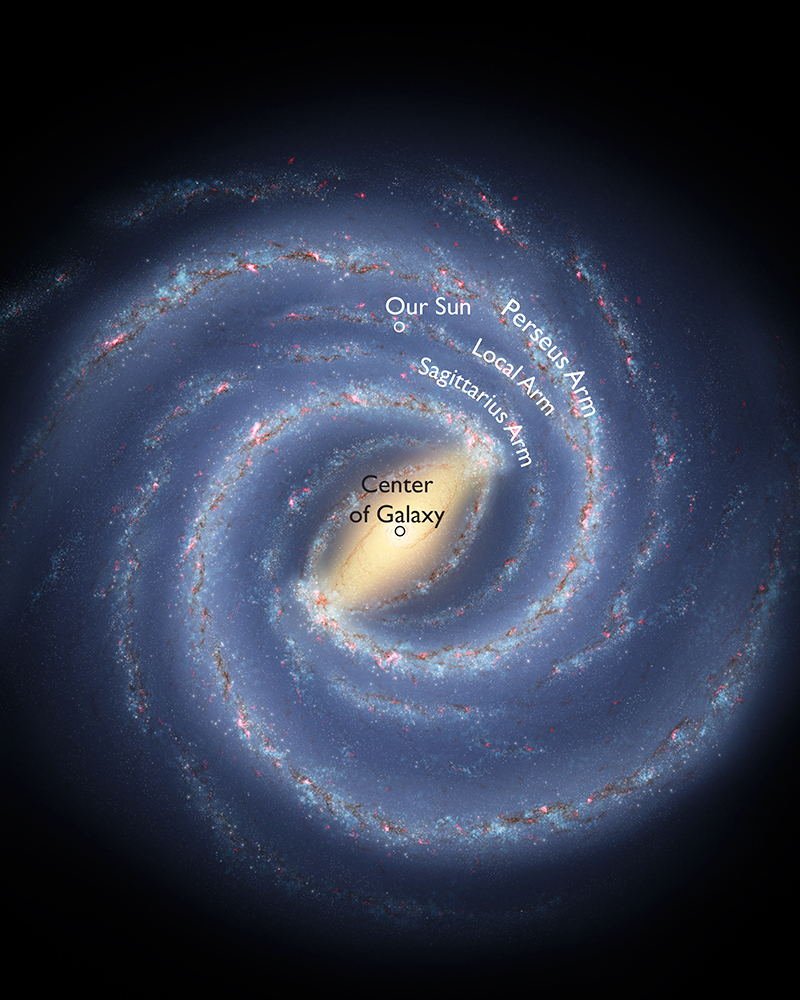

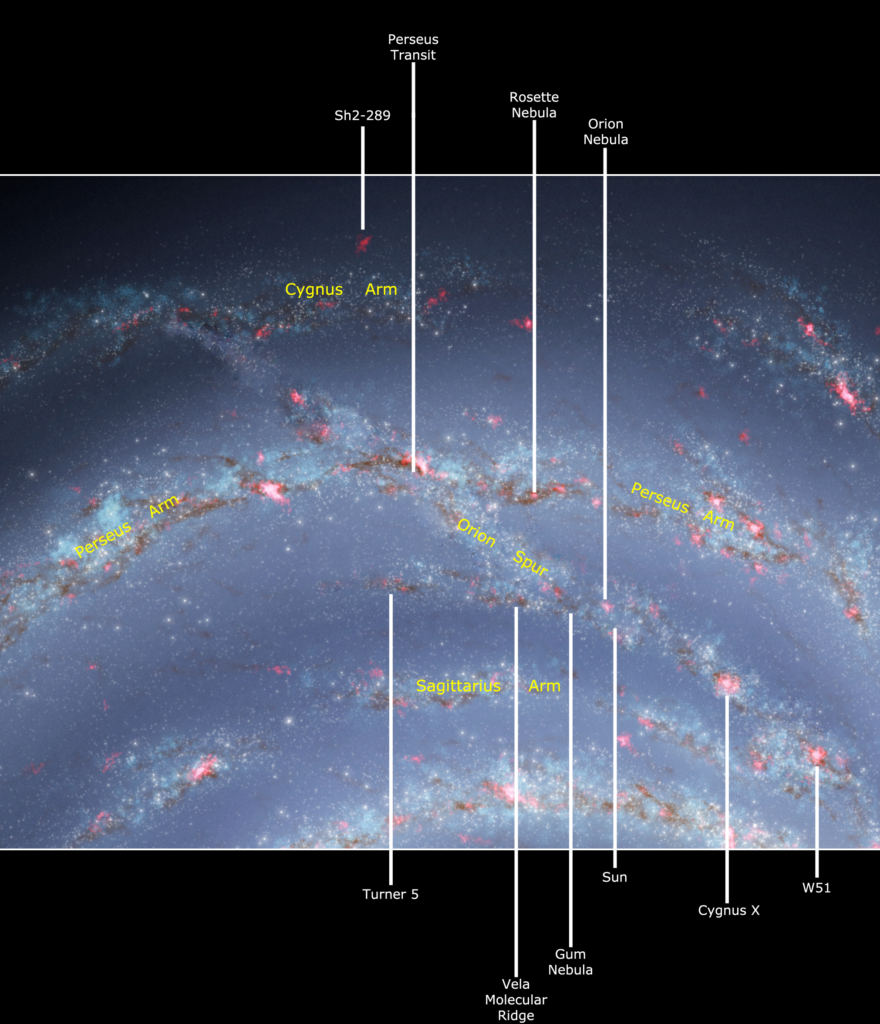

Why is the winter sky so rich in bright stars?

This is one of the most fascinating questions — and yes, it is related to the structure of the Milky Way.

When we look toward Orion and its neighbours, we are looking along one of the Milky Way’s nearby spiral arms, rich in young, massive stars. These stars:

- are intrinsically very bright,

- live short lives, so they don’t wander far from their birthplaces,

- and tend to form in clusters and associations, like the Orion region.

In summer, by contrast, we look toward the centre of the Galaxy — crowded with stars, but heavily obscured by dust. In winter, we look outward, into clearer space filled with nearby stellar associations. Fewer stars overall, perhaps — but more brilliant ones.

This is why winter evenings feel so dramatic: the sky is dominated not by sheer numbers, but by stellar heavyweights.

A season written in starlight

Winter skies reward patience. On a cold, still night, wrapped up under Northumberland’s dark skies, Orion and his companions tell a story of stellar birth, life, and death — written in colour and light across thousands of light-years.

It is a reminder that what we see above us is not random decoration, but a structured galaxy, and that for a few months each year, Earth’s night-time face is turned toward one of its most beautiful neighbourhoods.

Wishing you clear skies,

Dr Adrian Jannetta FRAS