Every August, the dark skies of Northumberland play host to a wonderful celestial display. Tiny flecks of cosmic debris light up the night as they burn through Earth’s atmosphere in one of the year’s most dependable meteor showers: the Perseids.

To the casual observer, they’re shooting stars. To astronomers, they’re a predictable, annual marvel. But the story of the Perseids is a journey through time, space, and fire, with roots that stretch from the depths of the solar system to the myths of ancient civilizations.

So, let’s look up—and look back—to uncover the science and history behind this summer sky show.

What is a meteor shower?

Before we dive into the specifics of the Perseids, let’s clarify what we’re actually seeing when we wish upon a shooting star.

A meteor is a bright streak of light in the sky caused by a small piece of space debris entering Earth’s atmosphere at high speed, often tens of kilometres per second. The intense friction causes the object to heat up and vaporise in a flash of light. If anything survives the plunge and lands on Earth, it’s called a meteorite, though that’s rare in most showers.

A meteor shower occurs when Earth passes through a stream of debris left behind by a comet. These bits of rock and ice are often no larger than grains of sand, but when they strike our atmosphere, their high velocity makes them flare brilliantly for a fraction of a second.

Meteor showers are typically named after the constellation where the meteors appear to originate from. This point in the sky is called the radiant. For the Perseids, the radiant lies in the constellation Perseus, which rises in the northeast on summer evenings – hence the name.

Meteors can be seen in any part of the sky during a meteor shower. The trails from meteors belonging to the same shower all trace back to the same radiant.

The radiant is an effect of perspective. Meteors in a shower tend to be coming in on parallel paths. Viewed from ground level – these paths converge to a vanishing point. You can see the same effect with railway tracks converging to a point in the distance.

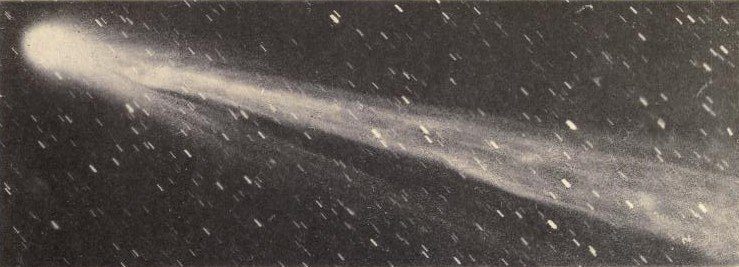

The Origins of the Perseids: Swift-Tuttle’s Dusty Trail

The Perseid meteor shower is the legacy of a comet called 109P/Swift-Tuttle, discovered independently by Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle in 1862. This comet is about 26 kilometres across—twice the size of the asteroid that contributed to the extinction of the dinosaurs—and it swings through the inner solar system every 133 years. In fact, Swift-Tuttle is the largest Solar System object (except the Moon) to repeatedly pass close to Earth. No need to worry though. Astronomers have ruled out any collisions with this comet for the next few thousand years!

Each time Swift-Tuttle visits, it leaves behind a trail of debris along its orbit. This debris disperses into a broad stream over centuries, and Earth crosses this stream every August. The bits that hit our atmosphere are often hundreds or even thousands of years old.

Though Swift-Tuttle last passed close to Earth in 1992, the trail it leaves is vast and dense enough to produce a shower every year. In fact, some years are particularly spectacular when Earth encounters one of the denser filaments of dust left behind during earlier cometary returns.

Where and when to watch

The Perseids typically peak around August 11th to 12th, but meteors can be seen from late July to late August. At their peak, observers under dark skies may see 50 to 100 meteors per hour—though rates vary with sky conditions, moonlight, and observer patience.

Here in Northumberland, we’re especially fortunate. Our Dark Sky Park status means we’re spared from the light pollution that spoils the view in cities. Whether you’re lying back in a garden hammock or stretched out on a hilltop, the Perseids reward those who give their eyes time to adjust and keep their gaze turned upward.

There’s no need for a telescope or binoculars—just a blanket, some warm clothes, and a wide view of the sky. Meteors can appear anywhere, but looking roughly 30–40 degrees away from Perseus (in the northeast) tends to yield the best views.

Every year is different. Sometimes, as in 2025, moonlight can lighten the sky preventing the faintest meteors from being seen. There is variability in the dusty stream from year to year. Sometimes it is denser than usual and other times it is less so. It is difficult to predict in advance: just go out and see what the shower does this year!

Why we love the Perseids!

The Perseids aren’t the most intense meteor shower—that title belongs to the Quadrantids in January, which can outburst to over 100 meteors per hour. But the Perseids are the best loved, and it’s not hard to see why:

- They arrive in summer: Clear, warm(ish) August nights are perfect for skywatching.

- They’re fast and bright: The meteors zip into the atmosphere at around 59 km/s, producing long trails, some with persistent glows or “trains.”

- They often include fireballs: Larger particles can create especially bright meteors, easily visible even in areas with some light pollution.

- They’re reliable: The shower delivers consistently year after year.

It’s also a shared experience. Across the Northern Hemisphere, people gather to watch this cosmic event; no ticket required, no telescope needed, just a patch of sky

Meteors in myth and memory

Long before we understood what caused meteor showers, people imbued them with meaning. Shooting stars were omens, messages from the gods, or the souls of the departed.

The Perseids themselves are sometimes associated with the tears of St. Lawrence, a Christian martyr burned alive in 258 AD. The story goes that St. Lawrence was placed on a large metal grill over a fire. His last words to his executioner we reputedly “Turn me over, I’m done on this side!” While this story very likely isn’t true, it is the reason St. Lawrence is known as the patron saint of cooks and comedians!

His feast day falls on August 10th, right when the shower peaks. In medieval Europe, the meteors were seen as the burning embers of his martyrdom falling from heaven.

In other cultures, meteors were symbols of fertility, warnings of war, or signs of change. The universality of watching lights fall from the heavens speaks to something deep and timeless in us.

Science from the Sky

While meteor showers are beautiful to watch, they also serve scientific purposes. By studying them, astronomers can:

- Map cometary debris trails and improve predictions about future encounters.

- Understand atmospheric entry: How different materials behave when they strike the atmosphere at hypersonic speeds.

- Track meteoroid streams that could pose a threat to satellites or even Earth.

- Reconstruct the evolution of comets, helping us understand the formation of the solar system.

In fact, studying meteor showers like the Perseids helps link everyday stargazing to the grand cosmic story of planetary birth and death.

One final wish…

The Perseids are a reminder that we live on a planet sailing through an active and ever-changing solar system. Once a year, we collide (peacefully, beautifully) with the dusty trail of an ancient comet. What we see is the briefest of fireworks: cosmic ash, igniting in our skies as it meets its end.

So this August, take some time to look up. You’re not just watching rocks burn. You’re witnessing a conversation between Earth and the cosmos, spoken in light.

And who knows? Make a wish. The universe might just be listening.

Clear skies!

Dr Adrian Jannetta FRAS