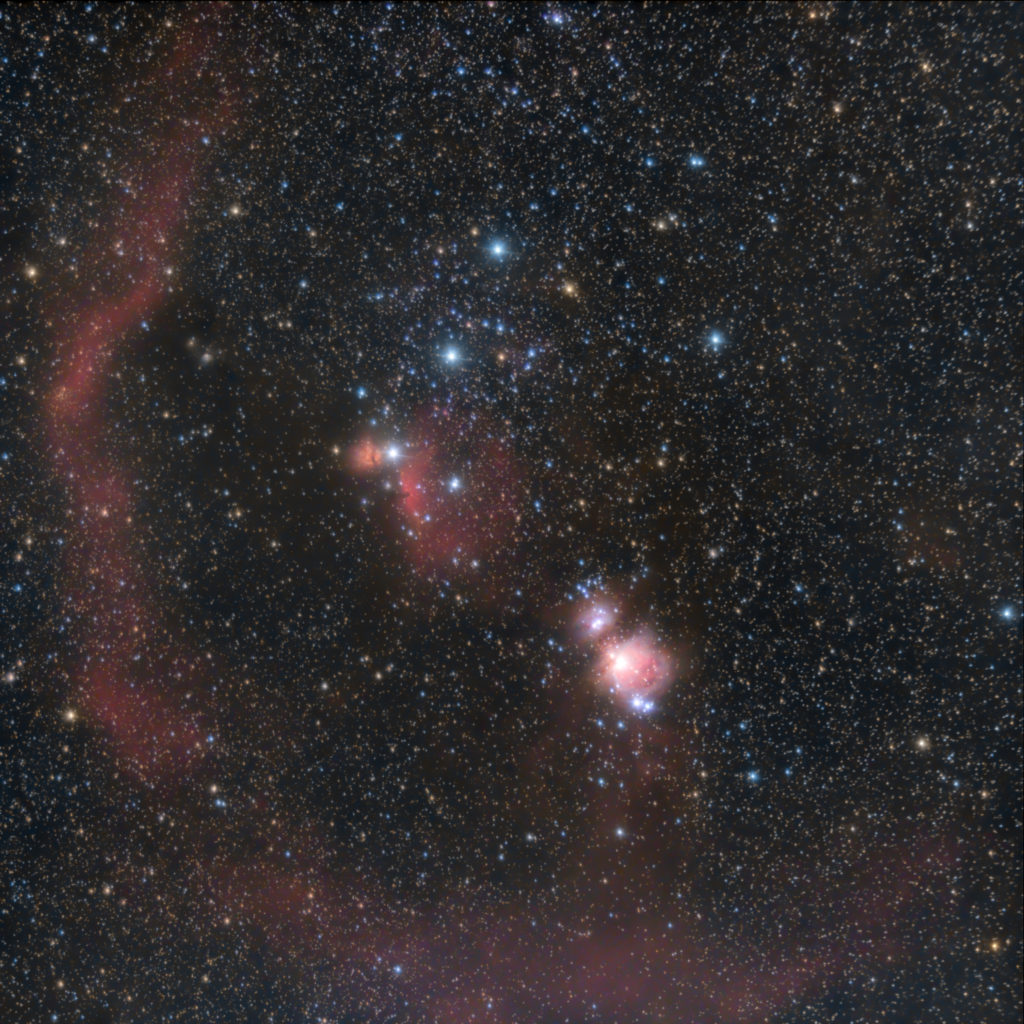

A couple of years ago I was waiting outside Ingram Village Hall for our guests to arrive for an evening of stargazing. It was a cold, clear evening in January with a light covering of snow and dimly illuminated by starlight. In the southern sky the stars of Orion were rising and I took a quick picture.

Orion was one of the first constellations I learned to find as a boy. Orion’s Belt – a prominent line of three stars – are very easy to recognise. In western sky culture Orion comes to us from ancient Greek mythology. There are several variations of his story. One of the most oft-told (thanks to the books of Patrick Moore) is one in which Orion boasted he could hunt and kill any animal in the world. This displeased Artemis, the goddess of nature, the wilderness and hunting. She sent a scorpion to teach Orion a lesson in humility. The scorpion duly stung Orion on the foot and killed him. Zeus raised both Orion and the Scorpion into the stars but tactfully placed placed them on opposite sides of the sky so they’d never encounter one another again.

The brightest star in Orion is usually Rigel, shining with a steely blue-white light to the south of the Belt. To the north is Betelgeuse, a striking orange-red star which varies in brightness over periods of years and which can very occasionally surpass Rigel in brilliance. Betelgeuse (usually pronounced Beetle-juice) is a star in the final stages of its existence and will explode as a supernova in the near future. Astronomically speaking, the near future may be anytime in the next thousand centuries or so! Given that the Milky Way is thought to produce around one supernova per century, the next supernova in our sky will probably not be Betelgeuse. However, if it does explode soon it will blaze as brightly as the full moon. At a distance of around 500 light-years, we are completely safe from any ill-effects.

Orion is home to a some of the nearest sites of star formation and star death in the Milky Way. Long exposure photos of the constellation reveal a interlinked clouds of gas and dust. It is especially prominent to the south of Orion’s Belt. To the naked eye three stars extend downwards (known as Orion’s Sword) and the middle one appears somewhat fuzzy. Binoculars and telescopes reveal the fuzzy star to be the famous Orion Nebula.

The Orion Nebula is located around 1,300 light-years away. The nebula is a stellar nursery – a place where new stars are forming from dense, collapsing clouds of gas and dust. At the heart of the Orion Nebula is a cluster of new stars whose four brightest members are known as the Trapezium. The Trapezium stars are much more massive and more luminous than our Sun. They were born a couple of million years ago and they’ll explode in just a few million more years. Live fast and die young, is the story for the most massive stars in the Milky Way. By comparison, the Sun is about halfway through a 10 billion year life. Intense light from the Trapezium stars is responsible for heating the surrounding hydrogen gas to the point where it fluoresces and glows.

Meanwhile, to the north of the Orion Nebula lies a stunning cosmic duo that has captured the fascination of stargazers for centuries: the Horsehead and Flame Nebulae.

The Horsehead Nebula, also known as Barnard 33, is one of the most recognizable dark nebulae in the sky. Appearing as a distinctive horse’s head silhouette against a backdrop of glowing hydrogen gas, it owes its shape to intricate, dust-filled columns sculpted by stellar winds and radiation. Just a short distance away, the Flame Nebula (NGC 2024) burns brightly, lit by the hot, young stars hiding at its core. This emission nebula gets its dramatic glow from ultraviolet radiation that excites the hydrogen gas, causing it to emit the brilliant red light we see in photographs. Like its neighbor, the Flame Nebula is also an active hub of stellar birth, giving astronomers an up-close view of the processes that shape our galaxy.

There is so much to see in Orion! I’ve spent several of the last few years taking images of the deepsky treasures within its borders. Each year I find something new or add to my growing collection of images.

Orion contains some of the brightest stars in the entire night sky. It straddles the celestial equator which means it is visible from every inhabited place on Earth for some of the year. The sky to the west (visible in northern autumn) and to the west (visible in northern spring) can look quite desolate in comparison!

Why does our Winter night sky with Orion and the surrounding stars look so brilliant? It turns out that it isn’t down to chance.

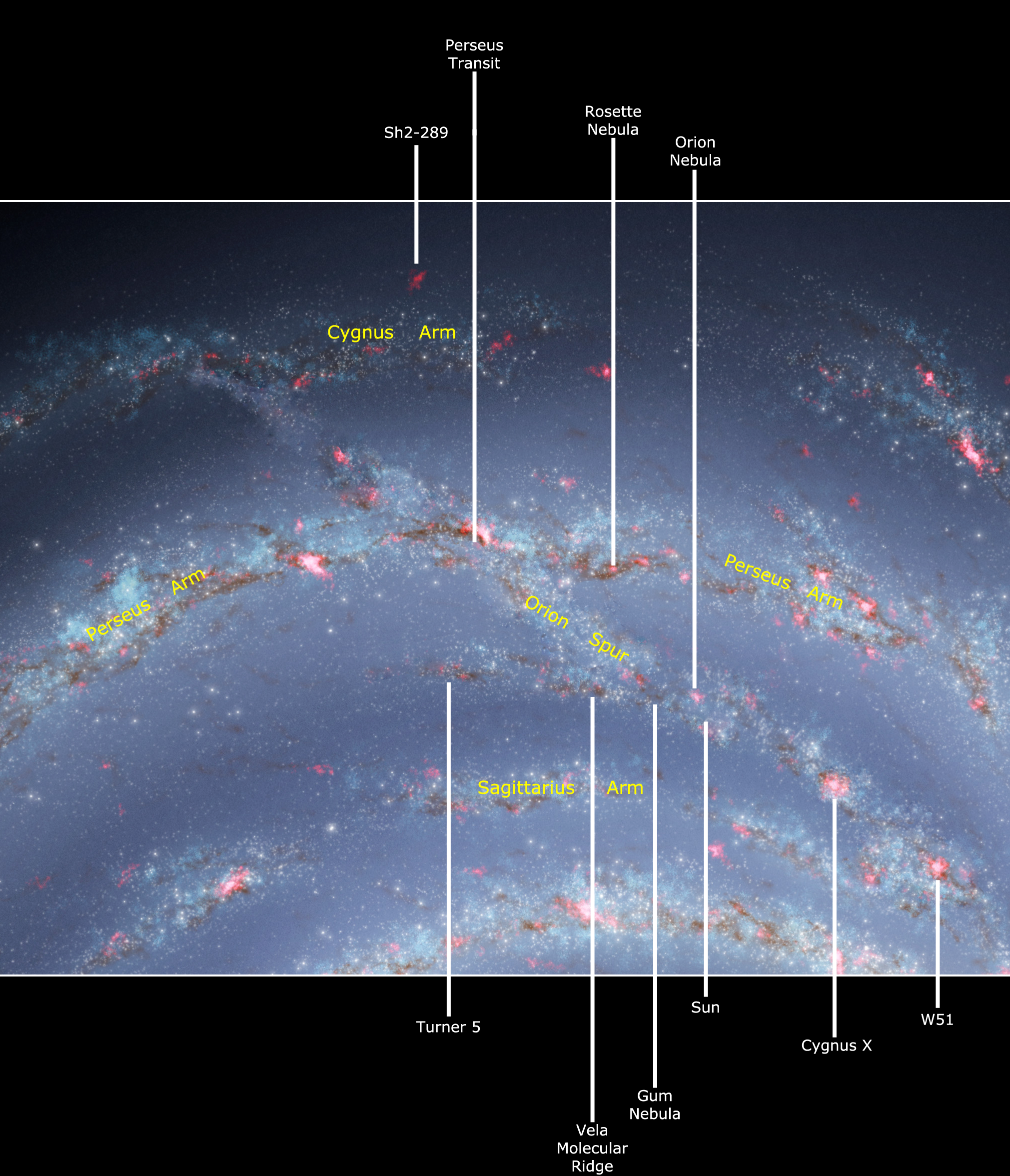

During the northern winter, the night-side of Earth is facing away from the centre of the Milky Way. Instead, we have a great view in the opposite direction towards another spiral arm of the Milky Way (the Perseus Arm). We also get to see right along another lane of stars – the Orion Spur, which stretches tens of thousands of light-years in that direction. The stars of Orion and its assortment of nebulae and star clusters belong to this feature. The sky in other directions does not have so many stars and the night sky at other times of the year can look a little less vivid by comparison.

Orion is a fixture of the Northumberland sky in winter. It will remain visible in dark skies until late March and then gradually disappear into the sunset twilight during April. Between now and then enjoy the view of the great Hunter and try to imagine the vast corridor of the stars at which Orion stands guard!

Wishing you clear skies,

Dr Adrian Jannetta FRAS