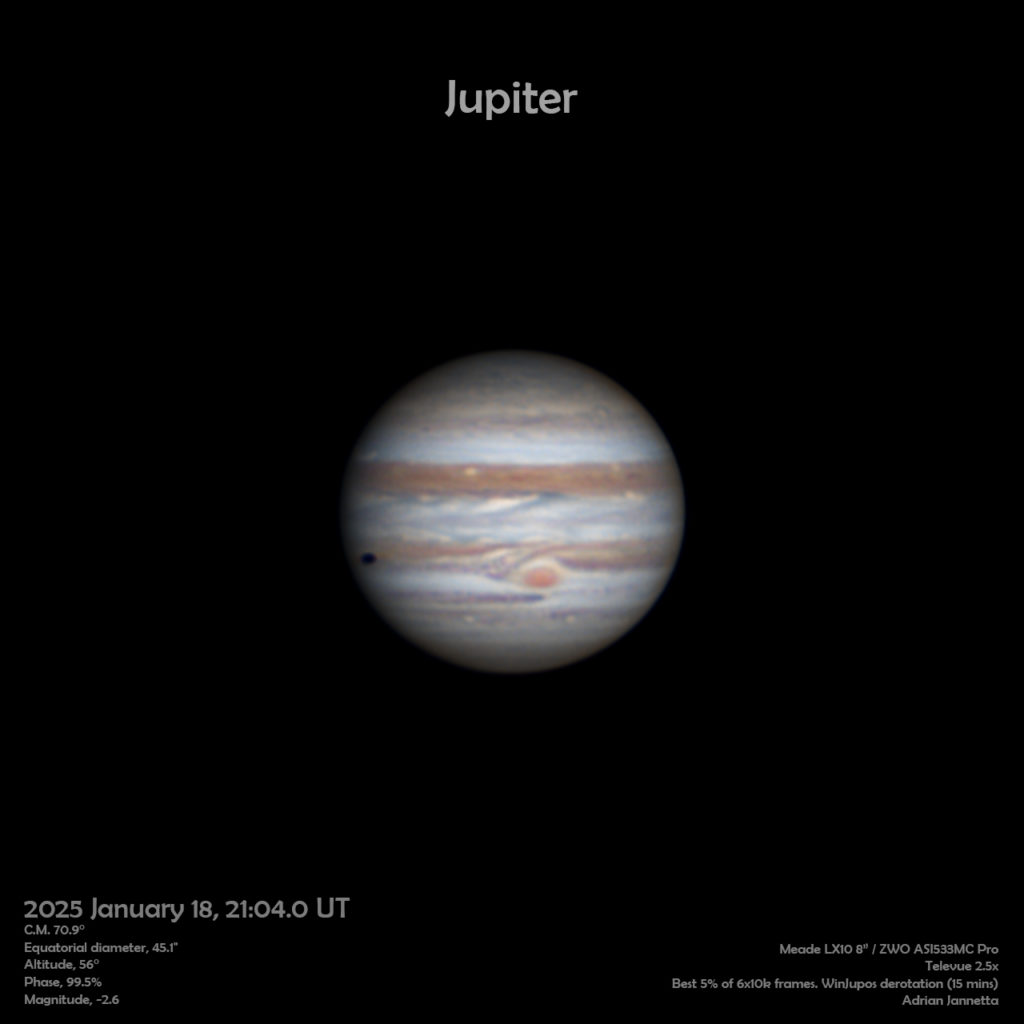

This month, Jupiter reached opposition. In simple terms, that means Earth lies between Jupiter and the Sun. Jupiter rises at sunset, is visible all night, and shines at its very brightest; a perfect target for winter stargazing from Northumberland’s famously dark skies.

At first glance Jupiter looks like a brilliant, steady star. But even a pair of binoculars reveals that this is not just a point of light, but a vast and complex world: the largest planet in the Solar System, with a family of moons and a history that helped reshape our understanding of the Universe.

Jupiter’s place in the solar system

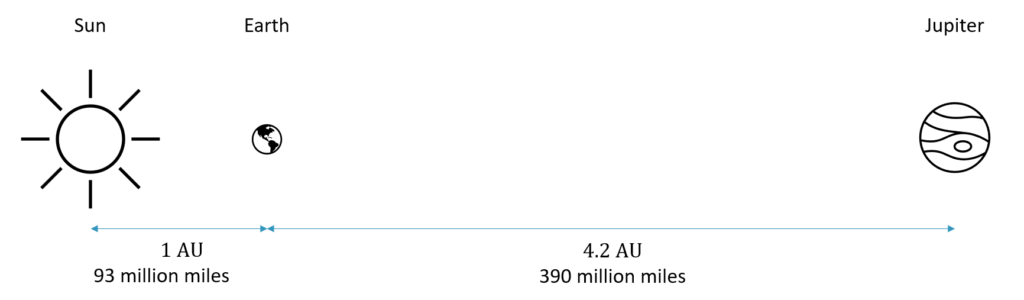

Jupiter orbits the Sun at an average distance of about 5.2 times the Earth–Sun distance. Astronomers call this unit an astronomical unit (AU), so Jupiter sits at around 5.2 AU, beyond the asteroid belt.

Because it is so far from the Sun, Jupiter takes a long time to complete an orbit — almost 12 Earth years for one Jovian year. As a result, it drifts slowly against the background stars, spending roughly a year in each zodiac constellation. In 2026 – you can find Jupiter among the stars of Gemini, the Twins.

Jupiter reaches opposition roughly every 13 months. After 12 months, the Earth is at the same place in its orbit that it was the previous year, but it takes another month for it to catch up and align with Jupiter which has moved 1/12 of the way around the Sun in that time.

Despite its enormous mass, Jupiter follows a fairly circular, stable path. That stability, combined with its gravity, has played a key role in shaping the structure of the Solar System.

A giant among planets

Jupiter really earns its reputation as the king of planets:

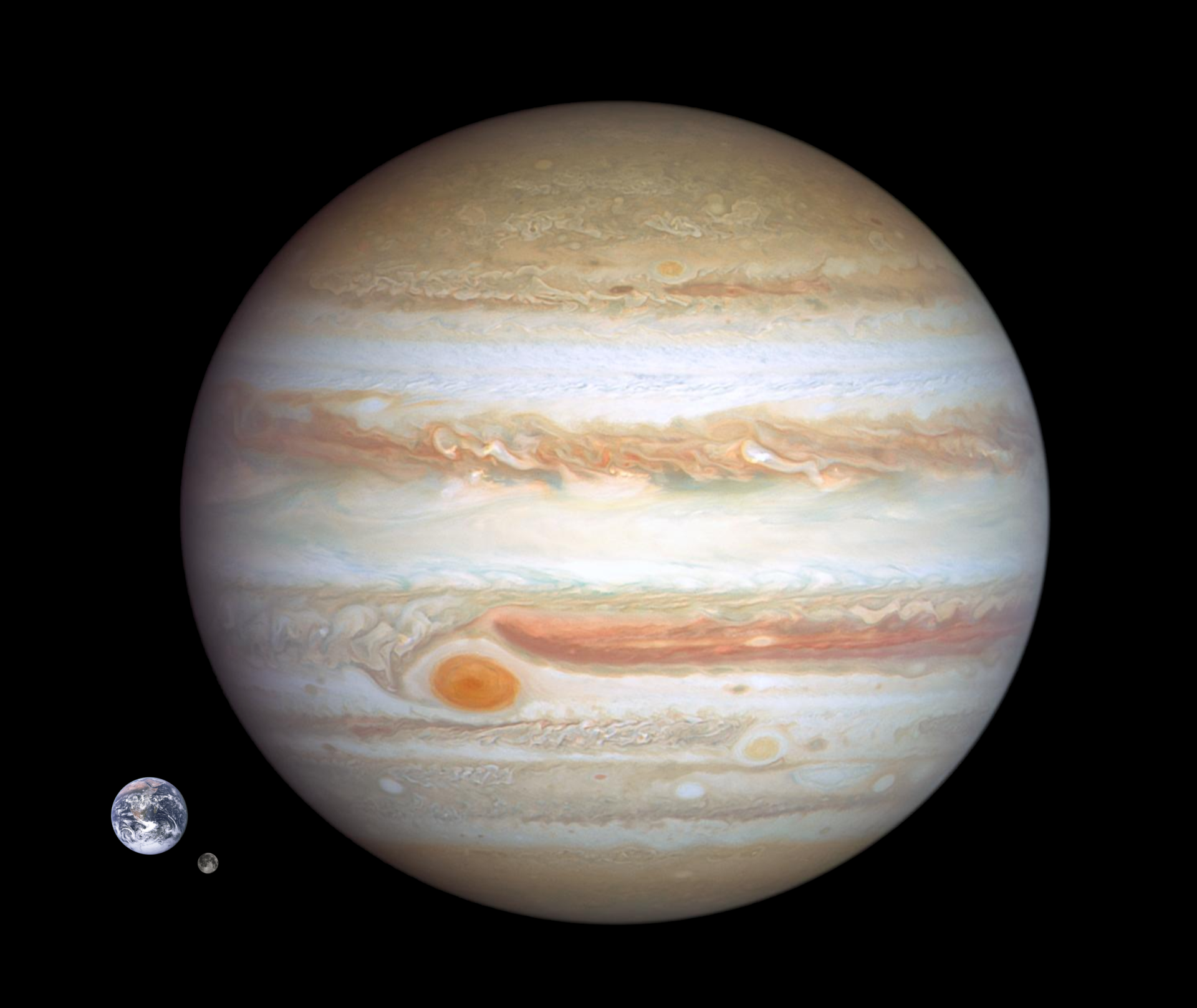

- It has more than twice the mass of all the other planets combined!

- It is 318 times the mass of the Earth.

- Over 1,300 Earths could fit inside it by volume

Yet Jupiter is still not massive enough to become a star. It would need to be about 80 times heavier to ignite nuclear fusion in its core. Instead, it remains a giant planet – made mostly of gas and liquid rather than rock.

Fast rotation and a squashed shape

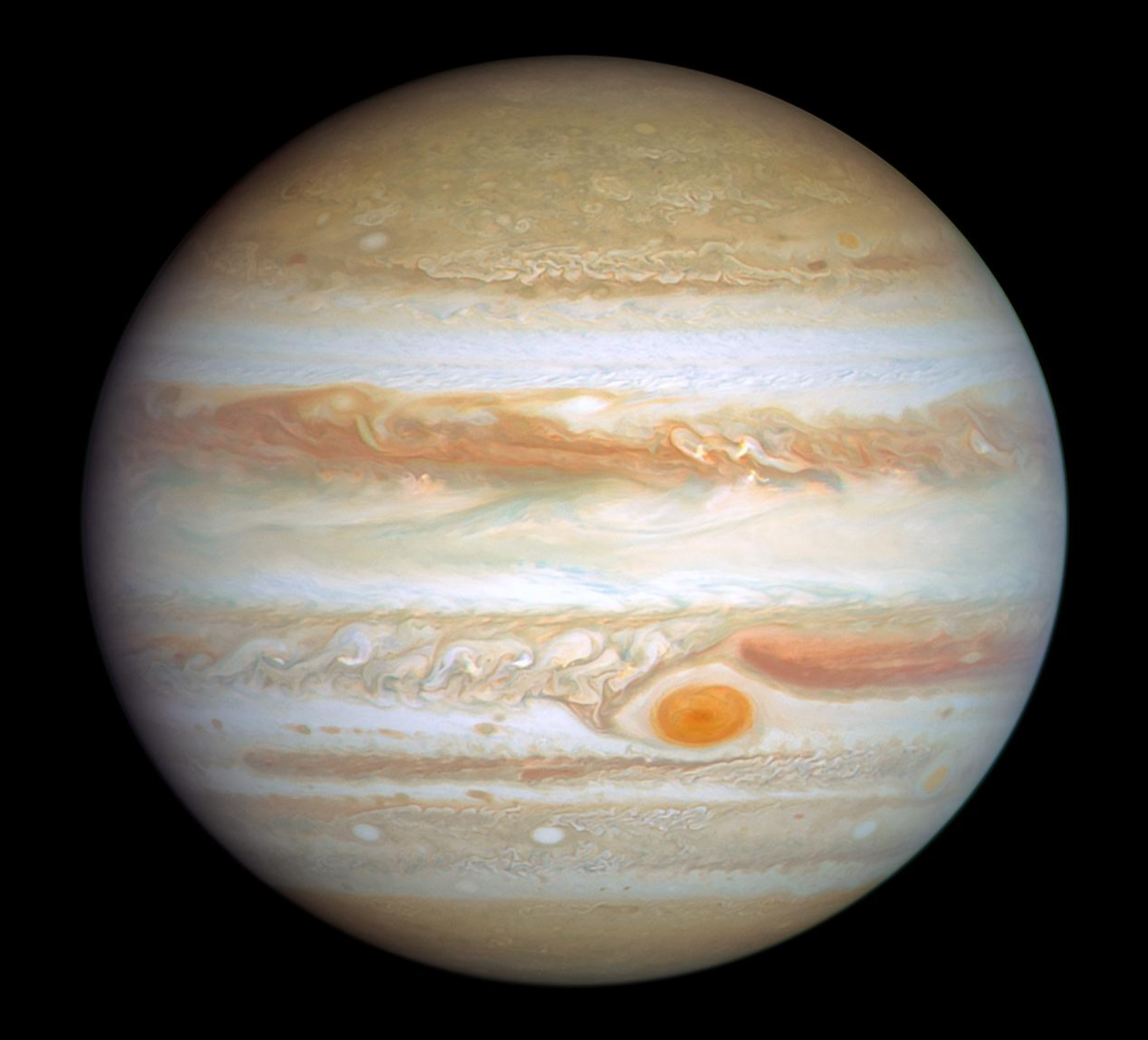

One of Jupiter’s most remarkable features is how fast it spins. A single day on Jupiter lasts just under 10 hours, making it the shortest day of any planet.

This rapid rotation has two clear effects:

- Jupiter is flattened at the poles and bulged at the equator, so it is slightly squashed rather than perfectly spherical.

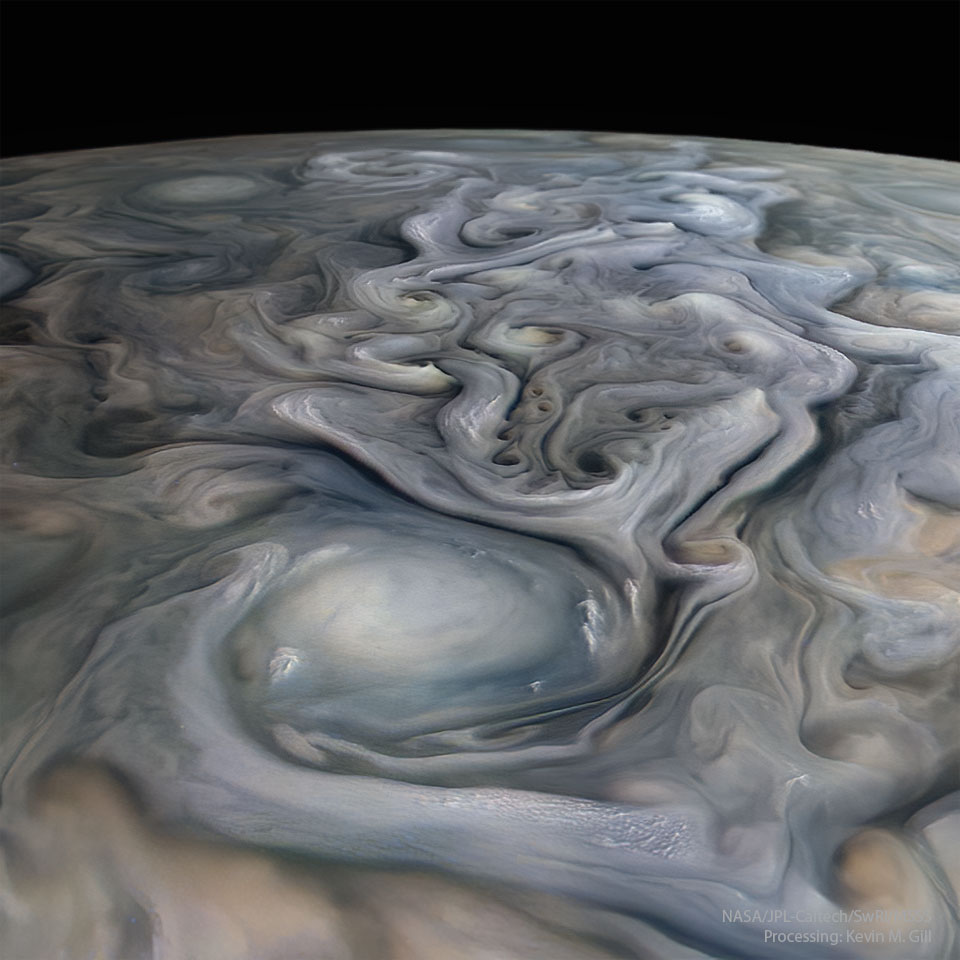

- The fast spin helps organise the atmosphere into the familiar dark and light cloud bands that wrap right around the planet.

Those bands are not surface features — they are vast systems of clouds, driven by powerful winds and deep internal heat.

What lies beneath the clouds?

Jupiter has no solid surface. If you could fall into it, you would simply descend through ever-thickening layers of gas and liquid.

The clouds we see are mostly made of hydrogen and helium, the same elements that dominate the Sun. Subtle colour differences come from small amounts of other chemicals, such as ammonia, stirred by turbulent weather.

Far below the clouds, the pressure becomes immense. Hydrogen is squeezed into a dense liquid, and then into an exotic state known as metallic hydrogen — hydrogen behaving like an electrical conductor.

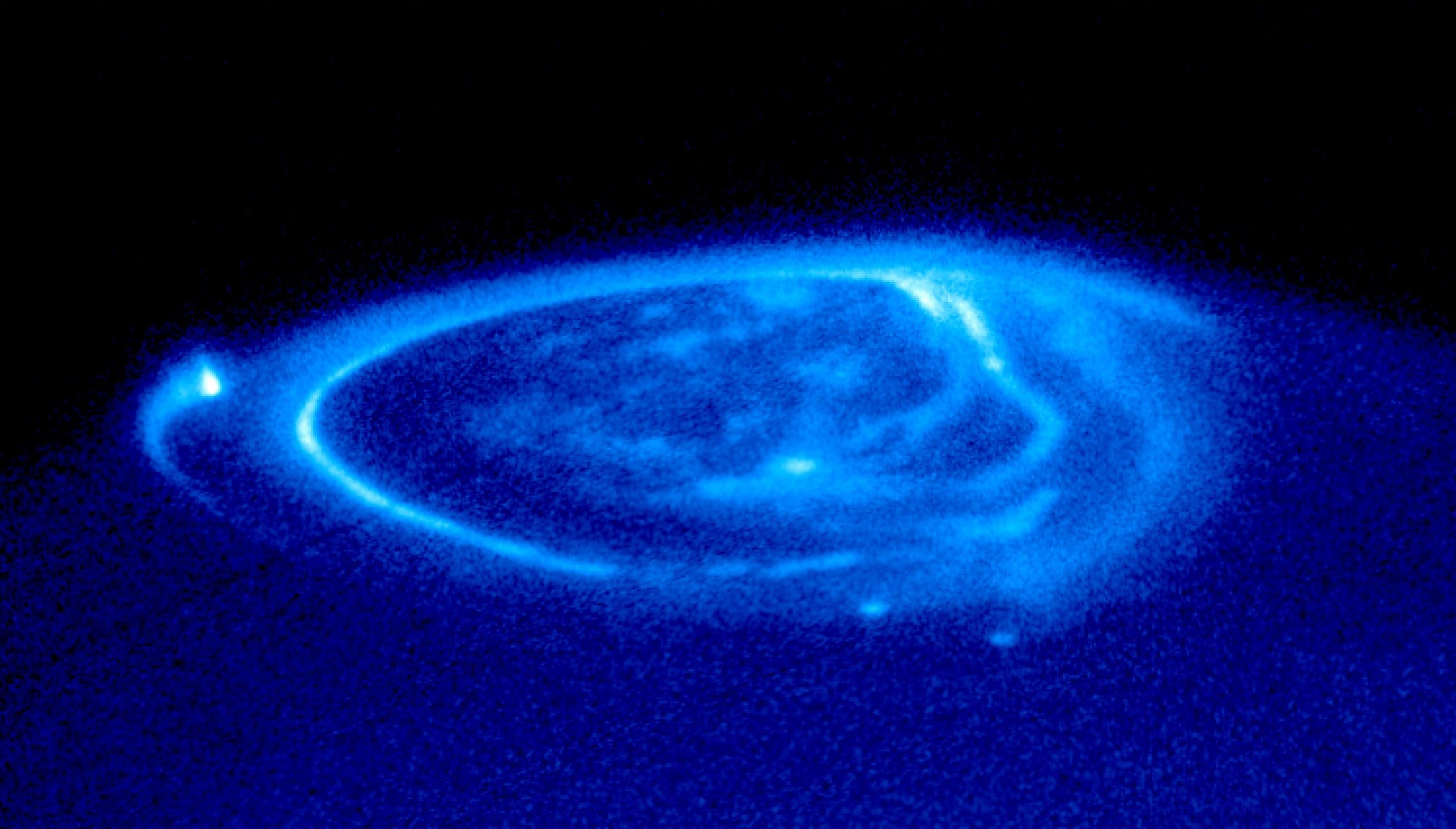

This strange material is thought to generate Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field, the strongest of any planet in the Solar System. As a result, Jupiter experiences auroras as the solar wind and solar storms sweep past it. Those aurora are much more energetic than those on Earth. However, the composition of Jupiter’s upper atmosphere means the emitted light is primarily ultraviolet and infrared, so they’d be mostly invisible to human eyes.

At its centre, Jupiter probably has a dense core made of heavier elements such as rock and ice. Recent spacecraft measurements suggest this core may be spread out or “fuzzy”, rather than a neat solid ball, and scientists are still working to understand its exact nature.

A turning point in astronomical history

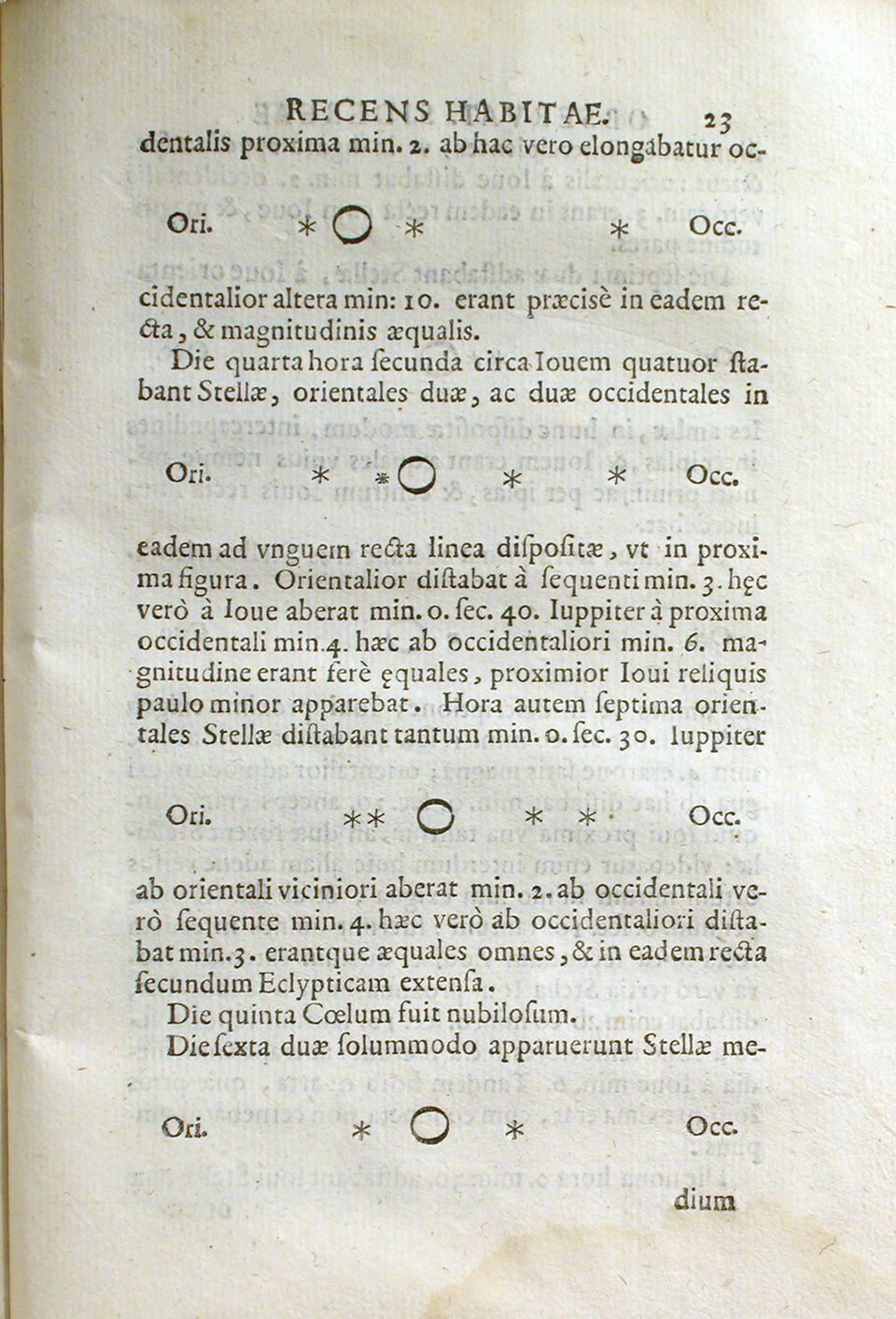

Jupiter has been known since ancient times, but its real impact on science began in 1610, when Galileo Galilei and other astronomers turned their newly invented telescopes towards it.

Galileo noticed four tiny points of light that changed position from night to night. These were moons orbiting Jupiter — clear evidence that not everything in the heavens circled Earth. It was the beginning of the end of belief in a geocentric universe. Galileo ultimately paid the price for these discoveries, but there is some consolation in knowing that those points of light are now known as the Galilean moons.

This simple observation helped overturn centuries of belief and changed humanity’s view of the cosmos. More about the Galilean moons shortly!

Jupiter up close: spacecraft exploration

Our detailed knowledge of Jupiter comes largely from visiting spacecraft. The first pioneers were NASA’s Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 in the early 1970s. They were trailblazers, proving that a spacecraft could safely pass through Jupiter’s intense radiation belts and sending back the first close-up measurements of its atmosphere, magnetic field, and enormous gravity. These early flybys paved the way for everything that followed.

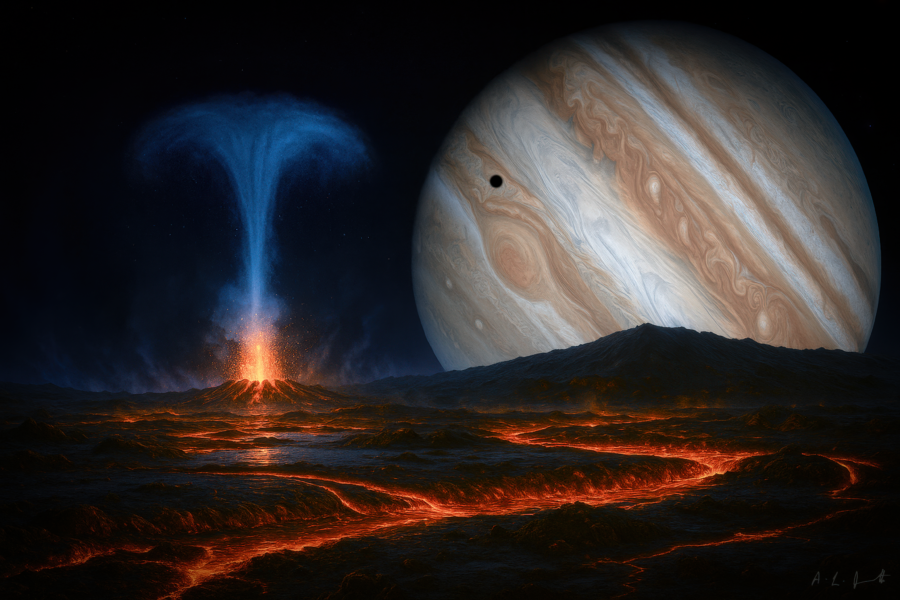

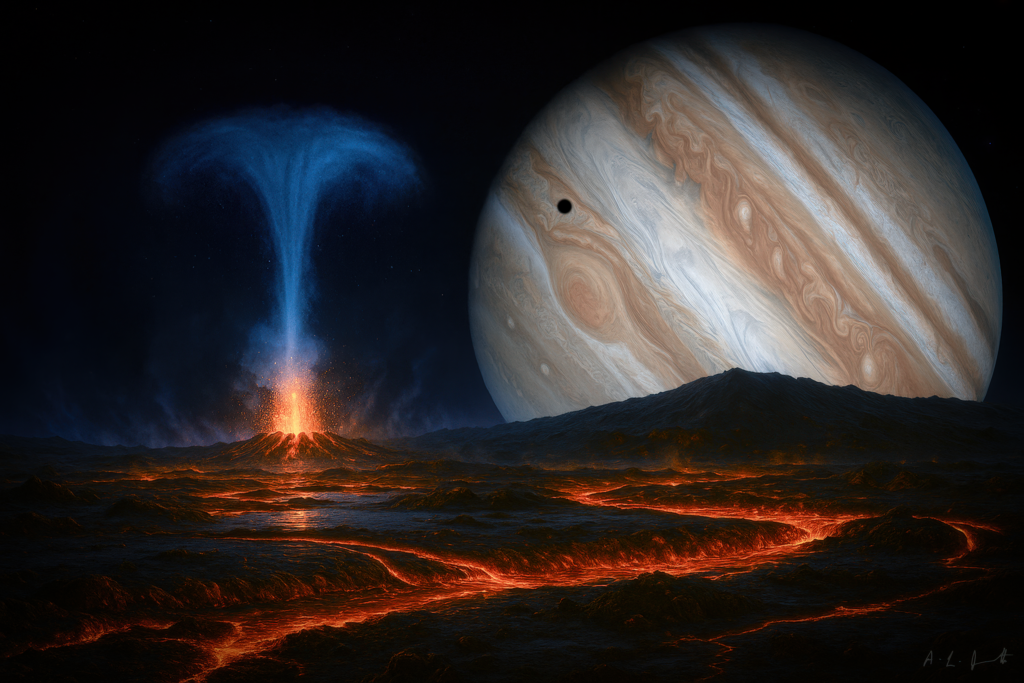

The real leap forward came with Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 in 1979. Voyager revealed Jupiter as a dynamic, violent world: swirling storms, lightning in the clouds, and active volcanoes on the moon Io. In the 1990s, the Galileo mission became the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter itself. Over eight years it studied the planet and its moons in detail, dropped a probe directly into Jupiter’s atmosphere, and transformed our understanding of Europa, strengthening the case for a hidden subsurface ocean.

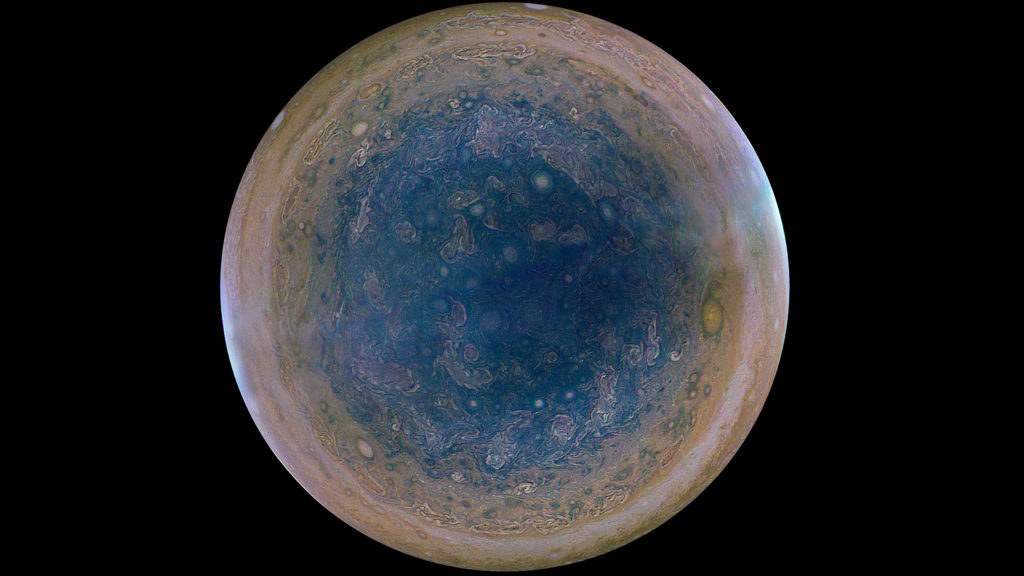

Today, Jupiter is being explored by Juno, which has been skimming just above the cloud tops since 2016. Juno is revealing what lies beneath the clouds, mapping Jupiter’s gravity and magnetic fields and giving new insights into its deep interior and mysterious, possibly “fuzzy” core. Looking ahead, the next chapter will be written by missions focused on Jupiter’s moons, especially icy Europa. ESA’s JUICE, launching this decade, will study Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in detail, while NASA’s Europa Clipper will repeatedly fly past Europa to investigate its ocean and habitability. Together, these missions show that Jupiter is not just a giant planet, but the gateway to some of the most intriguing worlds in the Solar System.

Moons that are worlds in their own right

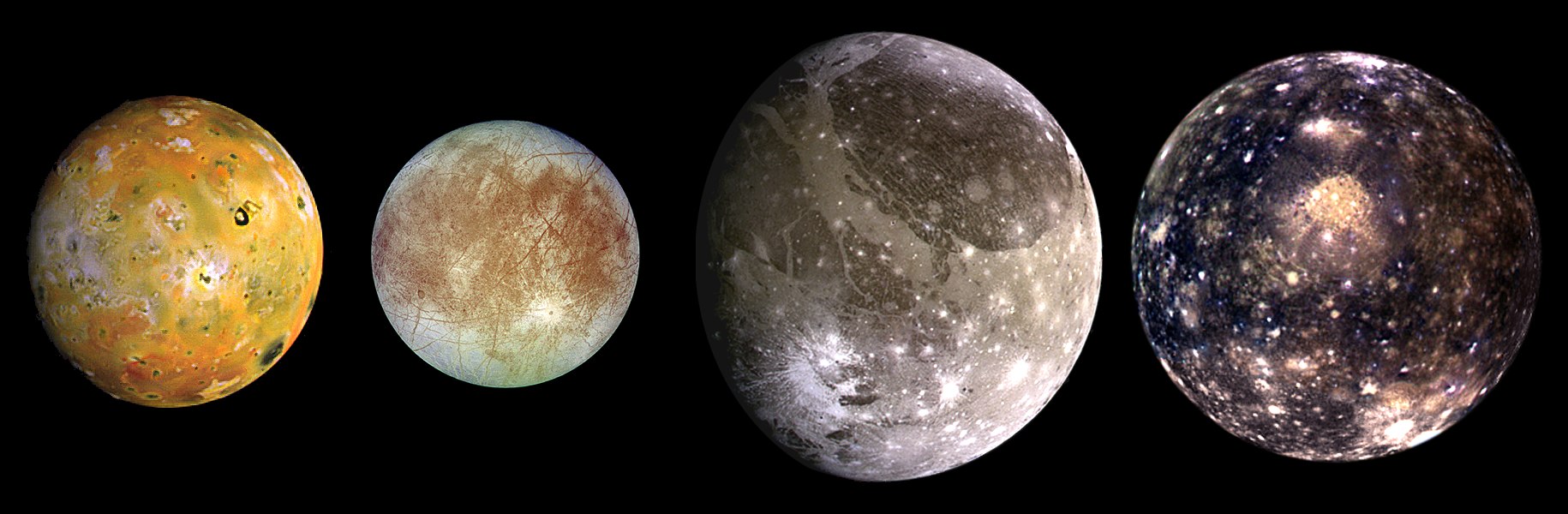

Each of Jupiter’s large moons is a fascinating world:

- Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System.

- Europa hides a global ocean beneath its icy crust, making it one of the most promising places to search for life beyond Earth.

- Ganymede is the largest moon of all — bigger than the planet Mercury — and even has its own magnetic field.

- Callisto is ancient and heavily cratered, preserving a record of early Solar System history.

Jupiter has A LOT of smaller moons! Some orbit between Io and the cloudtops of Jupiter. Beyond Ganymede there are the irregular moons; likely captured asteroids and comets, orbiting in random directions.

As of 2026 Jupiter has 97 known moons, including the 4 Galilean moons. There are likely many more awaiting discovery!

Jupiter the Solar System architect

Jupiter’s gravity has had a profound influence on the Solar System. It helped prevent a full planet from forming in the asteroid belt, instead leaving behind countless rocky fragments. It also shapes the orbits of comets, sometimes flinging them out of the Solar System, sometimes nudging them inwards.

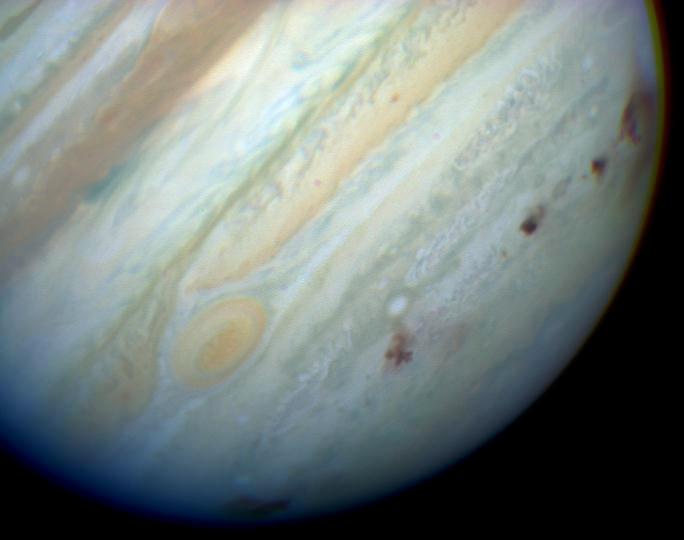

When comets or asteroids strike Jupiter, they leave visible scars in its cloud tops. In 1994 Jupiter was struck by a fragmented comet (named Shoemaker-Levy 9). These are dramatic reminders that Jupiter often absorbs impacts that might otherwise threaten the inner planets.

Observing Jupiter yourself

Jupiter outshines all the stars in the night sky and it’s the second brightest planet after Venus. It shines with a steady, yellowish hue. At opposition, the planet rises in the east at sunset and climbs high into the southern sky by midnight.

With binoculars – the four Galilean moons appear as tiny points, shifting position from night to night. There are many smartphone apps or websites which can help you to identify them.

With a small telescope Jupiter is one of the most rewarding objects in the night sky. The equatorial cloud bands become visible, and with patience and steady air, the famous Great Red Spot may come into view. Timings for spotting the GRS are also online.

You can watch the Galilean moons disappear into Jupiter’s shadow, cross in front of the planet, or re-emerge on the other side. These events are completely predictable and fun to watch; Jupiter feels alive and dynamic, even at the eyepiece.

A winter giant worth lingering over

At opposition, Jupiter is at its very best: bright, high in the sky, and rich in detail. It is a planet that connects naked-eye stargazing, the birth of modern science, cutting-edge space missions, and the long history of the Solar System itself.

On a clear winter night in Northumberland, pausing to watch Jupiter and its moons drift across the sky is a reminder that even a single bright object can open a window onto vast scales of space, time, and discovery.

Clear skies!

Dr Adrian Jannetta FRAS