Astronomers and clouds generally don’t get on. There is one exception.

When the long summer days of Northumberland finally give way to the soft hues of twilight, a rare and magical phenomenon can sometimes paint the northern skies – noctilucent clouds (NLCs). These elusive, night-shining clouds, with their ghostly blue-white tendrils, are among the highest clouds on Earth, forming nearly 50 miles above the ground at the edge of space. They’re a sight well worth staying up for if you find yourself in the region on a clear summer night.

What are Noctilucent Clouds?

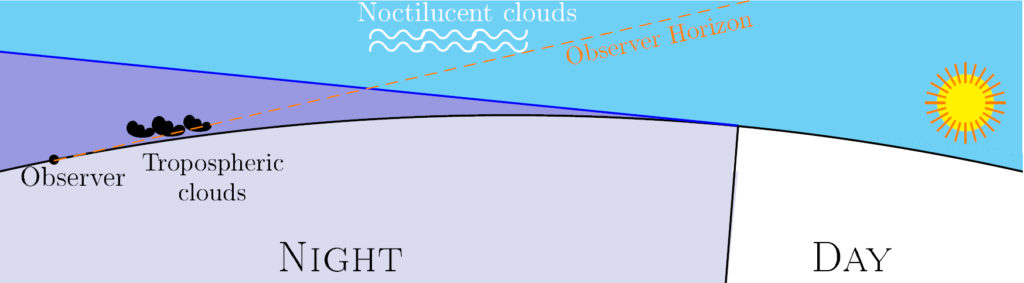

Noctilucent clouds are the highest clouds on our planet, forming in the mesosphere, roughly 76 to 85 kilometers (47 to 53 miles) above the ground. Unlike the everyday clouds we see at lower altitudes, these ethereal formations consist of tiny ice crystals – each about a thousandth the size of a typical raindrop. They only become visible when the Sun is between 6° and 16° below the horizon, meaning the sky must be dark enough for their faint glow to stand out, but their lofty altitude is still catching the last rays of sunlight.

The dark, unpolluted skies of Northumberland make it one of the best places in England to catch a glimpse of these fleeting clouds. Northumberland International Dark Sky Park, the largest protected dark sky area in Europe, offers a perfect backdrop for noctilucent cloud spotting. From the ancient ramparts of Bamburgh Castle to the wild shores of the Farne Islands, the county’s coastal and upland landscapes provide dramatic viewing locations for these high-altitude wonders.

When to look for them

Noctilucent clouds are a summertime phenomenon, typically appearing between late May and mid-August in the Northern Hemisphere. They are most often seen during the deep twilight hours – around an hour or two after sunset or just before sunrise. Peak activity usually occurs in June and July, when the mesosphere is at its coldest and the Sun’s angle is just right to illuminate these wispy ice clouds from below the horizon.

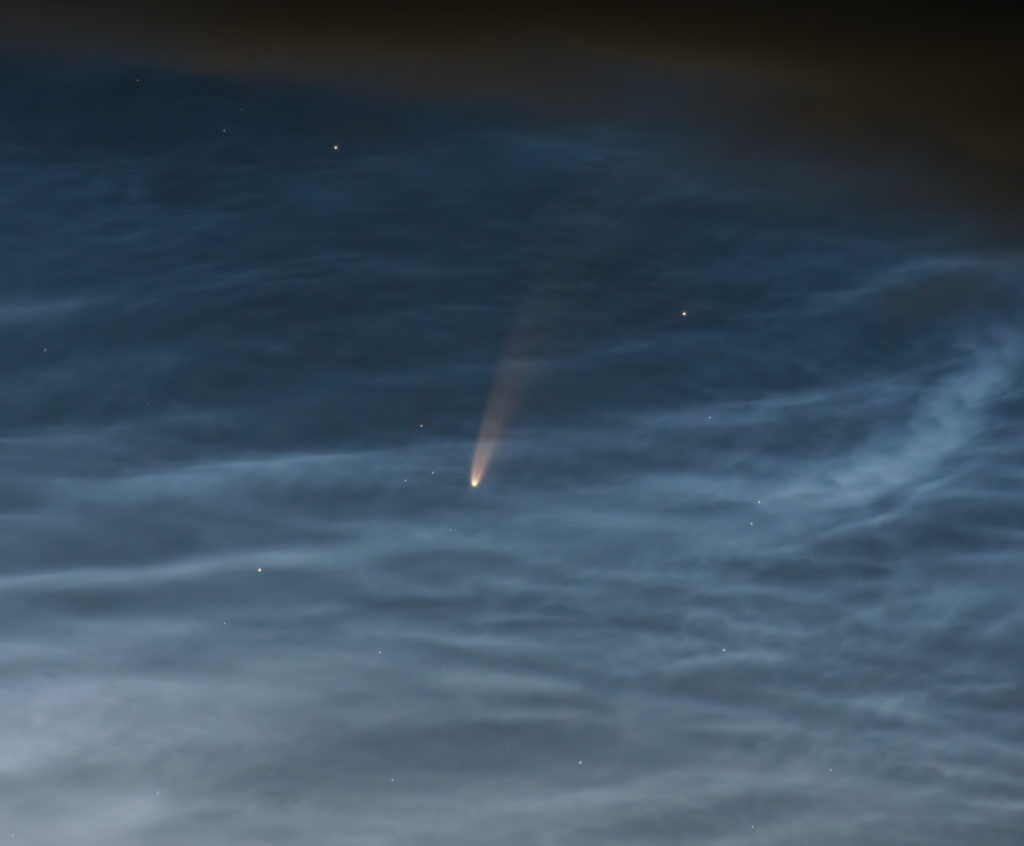

In the photo at the top of the article, those bright noctilucent clouds are hundreds of miles away to the north and still illuminated by the Sun. You can see some local clouds silhouetted against them – perhaps a few miles away and in full darkness. The picture was taken at local midnight but the NLCs were shining brightly.

What causes them?

NLCs form under rare and extreme conditions. To appear, they need ultra-cold temperatures (around –120°C), a small amount of water vapour, and tiny particles of dust on which ice can form. Interestingly, these clouds have become more common in recent decades, possibly due to changes in the upper atmosphere linked to human activity, like increased methane emissions and the cooling effects of carbon dioxide.

NLCs are in a tricky part of the atmosphere to study: too high for airplane or balloon borne experiments and far below the typical altitude of existing satellites. For many decades the origin of the dust was unexplained. Since noctilucent clouds were first noticed in the 1880s, not long after the eruption of Krakatoa, there was speculation that volcanic dust might be the seeds on which ice crystals form.

The mystery was solved by a dedicated satellite called AIM (Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere) which observed how sunlight filtered through the clouds. It discovered that the dust particles are meteor smoke. Meteors (also called shooting stars) are dusty debris from comets and asteroids orbiting the Sun which are swept up by the Earth as it revolves around the Sun. The shooting stars you occasionally glimpse at night are the seeds onto which these clouds form.

Noctilucent clouds are a kind of spaceweather!

What do they look like?

They have an eerie silver-blue colour with ripples and often a wave-like structure to them. They can be seen moving over periods of minutes. A particular display of NLCs may wax and wane – they don’t always remain visible for the entire night. And they aren’t visible every night.

Although they superficially resemble clouds like cirrus, or cirrostratus or cirrocumulus they are usually more sharply defined. Cirrus clouds tend to lose their definition and appear more fuzzy when viewed with binoculars whereas NLCs retain sharp edges on their structure. Cirrus clouds tend to fade into darkness eventually, whereas NLCs do not.

How to spot them

To maximize your chances of seeing noctilucent clouds in Northumberland:

- Find a spot with a clear view to the northern horizon.

- Avoid light pollution – dark skies are essential.

- Look for their distinctive, shimmering blue or silver tendrils, often with wave-like patterns.

- Check the weather – clear skies are a must.

- Be patient! These clouds can appear suddenly and drift slowly across the sky.

Why are they important?

NLCs are a recently discovered meteorological phenomenon. They were first sighted in the mid-1880s and have been consistently reported since. There are no definitive observations of them prior to that. Given how prominent these night-shining clouds it’s likely the clouds were absent from our sky until the late 19th century and they began to appear at a time when our atmosphere was beginning to change because of the addition of greenhouse gases from the industrial revolution.

As with the aurora, there is year-on-year variation in NLC sightings which are linked to solar activity. Unlike the aurora – it is almost reversed: in years with lots of solar activity (lots of spots) the Earth’s upper atmosphere is compressed and warmed. This suppresses the formation of noctilucent clouds. In quieter years, with small numbers of sunspots, our upper atmosphere in the summer atmosphere expands and becomes colder where NLCs form: we see more of them appearing as conditions become just right.

Noctilucent clouds and climate change

The mesosphere, where NLCs form, is the driest part of the Earth’s atmosphere. Much drier than the Sahara desert in fact! It shouldn’t be easy to form clouds in those conditions.

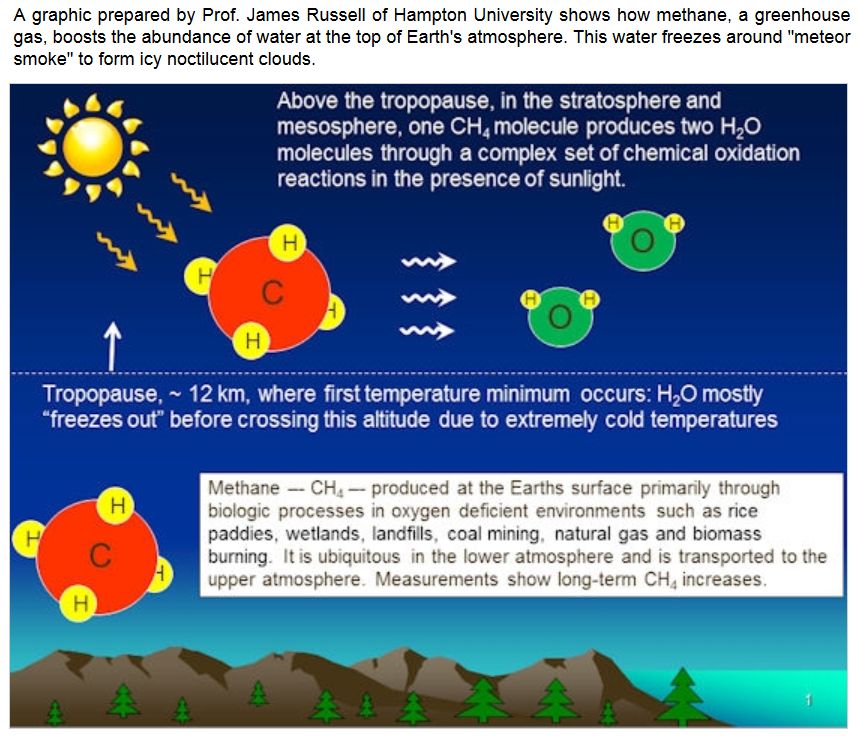

While methane is often discussed in the context of climate change, it also has a surprising connection to noctilucent clouds. Methane is produced naturally in wetlands such swamps, marshes, and peat bogs. However, it has increasingly been produced by people through agriculture and fossil fuel burning.

When methane reaches the upper atmosphere, it undergoes a series of chemical reactions that produce water vapour.

These steps include oxidation by hydroxyl radicals (OH) and photolysis by ultraviolet light, ultimately resulting in the formation of water molecules. In fact, a single methane molecule can yield two water molecules as it breaks down. This extra water vapour at high altitudes can then freeze onto the meteor dust particles to form noctilucent clouds.

The long-term trend seen over the past century is that the frequency and intensity of NLCs is increasing. Noctilucent clouds may well be tracers of climate change writ large across our summer night sky.

A night to remember

Whether you’re a seasoned stargazer or a casual visitor, witnessing noctilucent clouds can be a surreal experience – a fleeting glimpse into the mesosphere, where the atmosphere brushes the edge of space. So, if you find yourself in Northumberland this summer, don’t miss the chance to look up and catch this natural wonder. It’s a reminder of the beauty that lies just beyond our everyday skies.

Clear skies!

Dr Adrian Jannetta FRAS